Definition

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease that typically affects the lungs, but it can also impact other areas, including the bones, brain, intestines, and skin. Orifice tuberculosis specifically refers to tuberculosis infections affecting areas near the nose, mouth, or anus.

Causes

Orifice tuberculosis results from infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a rod-shaped bacterium with an acid-containing cell wall, detectable via acid-fast bacillus (AFB) testing. The bacteria are generally transmitted through airborne droplets when an infected person coughs or sneezes, and they can survive for hours in open air. Once inside the body, the bacteria may spread to other organs, including the skin, via the bloodstream or nearby infected tissues. Orifice tuberculosis can also develop through autoinoculation, where the infection spreads from adjacent organs.

Risk Factors

This type of tuberculosis is most prevalent in people with weakened immune systems due to certain diseases or medications. Conditions like HIV/AIDS, diabetes, cancer, or other immune-related diseases can impair the body’s defenses. Additionally, medications used for autoimmune conditions or in organ transplant recipients may further suppress the immune response, increasing susceptibility to orifice tuberculosis.

Symptoms

Skin tuberculosis symptoms are generally categorized into four major groups:

- Exogenous Skin Tuberculosis: Includes types such as chancre tuberculosis and verrucous tuberculosis cutis.

- Endogenous Skin Tuberculosis: Results from infection spreading from nearby organs and includes conditions like scrofuloderma, orifice tuberculosis, and some cases of lupus vulgaris.

- Tuberculid: Includes forms such as papulonecrotic tuberculid and lichen scrofulosorum.

- Secondary Skin Tuberculosis: Occurs as a result of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) immunization.

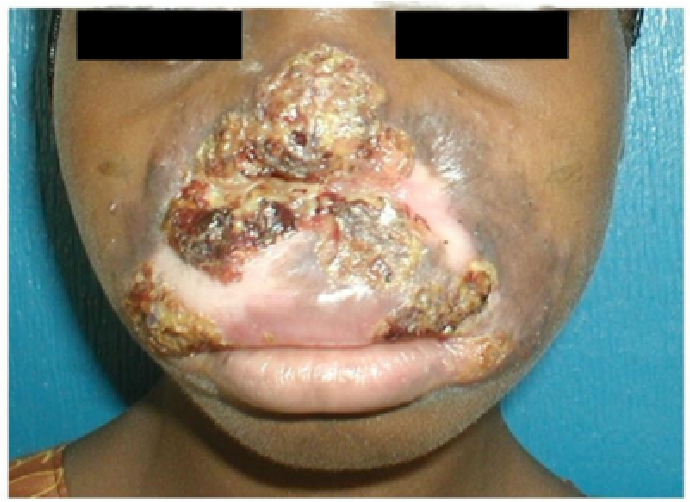

Orifice tuberculosis itself is characterized by painful nodules located at the transition between the inner and outer skin layers, such as on the lips, nose, or near the anus. This disease can also cause shallow ulcers and is often associated with a more severe tuberculosis infection elsewhere in the body. Typical symptoms may include a persistent cough with phlegm, night sweats, weight loss, fever, coughing up blood, chest pain, and fatigue.

Diagnosis

Orifice tuberculosis is diagnosed by analyzing the patient’s medical history, symptoms, and specific tests. Medical history may reveal a compromised immune system due to conditions like AIDS, poorly controlled diabetes, cancer, or end-stage kidney failure, as well as frequent injection needle use or medications that lower immune defenses.

Further examination may include a tuberculin test, which involves injecting tuberculosis bacterial protein into the skin to observe any immune response. A positive result indicates either active tuberculosis or prior exposure; however, in cases of extremely low immunity, this test may produce a false negative.

Doctors may also perform a biopsy on tissue from any ulcers or sores. This biopsy allows for three types of analysis: AFB (acid-fast bacillus) testing, histopathology, and bacterial culture. The AFB test detects bacterial presence under a microscope, while histopathology directly examines infected skin cells, and a culture test at cold temperatures assesses Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth. Culture testing remains the gold standard for identifying bacteria in skin lesions.

Additional diagnostic tools might include a chest X-ray to assess lung health and a sputum test for AFB and bacterial culture.

Management

The treatment for orifice tuberculosis mirrors that of other forms of tuberculosis and typically involves a combination of multiple antibiotics. The most commonly prescribed medications include rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. In some cases, injectable streptomycin may also be utilized. If drug susceptibility testing (DST) or culture results indicate resistance to specific antibiotics, alternative medications can be employed.

Antibiotic treatment consists of two distinct phases:

- Intensive Phase: The goal of this phase is to rapidly reduce the levels of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the body. Patients are usually prescribed a regimen that includes rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, and occasionally streptomycin. This phase typically lasts for 2 consecutive months, during which these medications are taken daily.

- Continuation Phase: This phase aims to completely eliminate any remaining tuberculosis bacteria from the body. The standard regimen during this phase generally includes rifampicin and isoniazid, administered daily or three times a week for an additional 4 months. Research indicates that a total treatment duration of 6 months (comprising 2 months in the intensive phase and 4 months in the continuation phase) is effective for recovery from orifice tuberculosis.

While there are numerous antibiotics available for tuberculosis treatment, they are often prescribed in fixed-dose combinations (FDCs). These combinations contain four antibiotics for the intensive phase (including injectable streptomycin) and two for the continuation phase, with dosages adjusted according to the patient's weight.

To effectively manage orifice tuberculosis, patient adherence to the prescribed medication schedule is crucial. This necessitates a strong commitment from the patient, as well as collaboration from their close contacts and healthcare providers. A drug supervisor (PMO) can be appointed to monitor the patient's medication intake, ensuring that doses are taken correctly and punctually, without any regurgitation.

The medications used in treatment may produce side effects that can range from mild (such as harmless red urine or nausea) to severe (including hepatitis, allergic reactions, or neurological issues). Should any side effects occur, it is important for patients to consult their healthcare provider for guidance on how to manage these reactions while continuing treatment.

Complications

Orifice tuberculosis, if treated promptly, typically resolves without leaving scars. However, delays in treatment or neglecting medical care may lead to further spread of the infection.

Prevention

Preventing orifice tuberculosis involves several key measures:

- BCG Immunization: Administered to newborns up to two months old, this vaccine injects weakened tuberculosis bacteria under the skin to train the immune system to recognize and combat the bacteria. It is less effective in children over two months of age.

- Tuberculosis Screening: Early identification, isolation, and management of tuberculosis cases, especially in those with immune challenges, can help prevent transmission.

- Immune System Management: For individuals with conditions like HIV/AIDS or diabetes, regular treatment is essential to maintain sufficient immune defenses against tuberculosis. For diabetic patients, blood sugar control is vital to minimize the spread of tuberculosis throughout the body, including to areas affected by orifice tuberculosis. For individuals on immunosuppressive drugs, doctors may prescribe antibiotics as a preventive measure against orifice tuberculosis.

When to See a Doctor?

If you have a weakened immune system or are taking immunosuppressive medications, regular check-ups are essential to monitor for tuberculosis. You should also consult a doctor if you experience painful ulcers on areas like your lips, nose, or anus, as these could be indicative of orifice tuberculosis, though similar symptoms can arise from other conditions.

Looking for more information about other diseases? Click here!

- dr. Alvidiani Agustina Damanik

Ali, G., & Goravey, W. (2021). Primary tuberculosis cutis orificialis; a different face of the same coin. Idcases, 26, e01305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01305

Charifa, A., Mangat, R., & Oakley, A. (2021). Cutaneous Tuberculosis. Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 12 June 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482220/.

Mansfield, B., & Pieton, K. (2019). Tuberculosis Cutis Orificialis. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 6(10). https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofz428

Ngan, V., & Oakley, A. (2021). Cutaneous tuberculosis (TB) | DermNet NZ. Dermnetnz.org. Retrieved 12 June 2022, from https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-tuberculosis.