Definisi

Hepatitis B merupakan infeksi hati yang disebabkan oleh virus hepatitis B (VHB atau HBV). Penyakit ini dapat bersifat akut dan kronik, dan dapat mengancam nyawa jika tidak tertangani dengan baik. Pada tahun 2019, World Health Organization (WHO) memperkirakan terdapat 296 juta orang di seluruh dunia yang hidup dengan infeksi kronik hepatitis B, dengan 1,5 juta kasus baru per tahunnya. Pada tahun yang sama, diperkirakan infeksi hepatitis B berperan dalam 820.000 kematian di seluruh dunia, yang pada umumnya terjadi akibat komplikasi infeksi ini.

Penyebab

Hepatitis B disebabkan oleh virus hepatitis B (VHB), sebuah virus dari keluarga Hepadnaviridae. Virus ini dapat ditularkan secara vertikal (dari ibu ke anak) atau horizontal (paparan terhadap darah orang yang terinfeksi). Paparan secara vertikal biasanya terjadi apabila ibu terinfeksi pada saat kehamilan. Sementara itu, paparan secara horizontal pada umumnya terjadi akibat luka tertusuk jarum suntik, penggunaan tato atau tindik, pajanan terhadap darah yang terinfeksi, ludah, serta cairan menstruasi dan vagina pada perempuan, serta semen pada laki-laki. Paparan ini juga dapat terjadi akibat penggunaan jarum suntik secara berulang, baik pada fasilitas kesehatan, komunitas, ataupun pada pengguna narkotika, psikotropika, dan zat-zat adiktif (NAPZA). Selain itu, paparan ini sering terjadi pada orang-orang yang memiliki pasangan seksual lebih dari satu.

Virus ini dapat memperbanyak diri hanya di dalam sel-sel hati (hepatosit), yang kemudian dikeluarkan ke darah dan cairan tubuh lainnya. Infeksi dapat terjadi secara akut, dalam waktu yang sebentar, kemudian sembuh secara spontan. Pada kasus seperti ini, tubuh membentuk kekebalan alami terhadap virus hepatitis B. Namun, infeksi juga dapat menjadi kronik, yang pada umumnya tidak bergejala hingga mencapai fase reaktivasi. Fase reaktivasi merupakan fase ketika materi genetik virus meningkat jumlahnya secara drastis dan hati mengalami peradangan kembali. Hepatitis B yang didapatkan sebelum usia 5 tahun berisiko menjadi kronik pada 95% kasus, sementara hepatitis B yang didapatkan pada usia dewasa menjadi kronik pada 5% kasus.

Virus ini dapat bertahan di luar tubuh selama minimal 7 hari. Pada rentang waktu tersebut, infeksi masih dapat terjadi apabila virus masuk ke dalam tubuh seseorang yang belum divaksin. Virus ini membutuhkan waktu 30-180 hari dari masuknya virus sampai menyebabkan gejala, namun virus dapat terdeteksi mulai pada hari ke-30 hingga 60 setelah infeksi.

Faktor Risiko

Faktor risiko hepatitis B adalah lahir di wilayah dengan angka kejadian infeksi lebih dari 2% (Indonesia merupakan salah satunya), tidak divaksin hepatitis B saat lahir, penggunaan obat atau NAPZA dengan jarum suntik, laki-laki yang berhubungan seks dengan laki-laki, penggunaan obat-obatan untuk menekan sistem kekebalan tubuh seperti pada penyakit autoimun (penyakit yang menyebabkan sel kekebalan tubuh menyerang sel diri sendiri), penerima transfusi darah, bayi yang lahir dari ibu yang positif terinfeksi hepatitis B, penderita gagal ginjal stadium akhir, penderita HIV/AIDS, infeksi hepatitis C, tinggal serumah atau berhubungan seks dengan penderita hepatitis B, memiliki pasangan seks lebih dari satu, penyakit menular seksual, pekerja fasilitas kesehatan yang berisiko terpapar dengan darah atau cairan tubuh yang terkontaminasi darah, penghuni fasilitas rehabilitasi, serta penderita diabetes yang belum pernah divaksinasi hepatitis B.

Gejala

Pada umumnya, orang yang baru saja terinfeksi virus hepatitis B tidak mengeluhkan gejala apapun. Pada infeksi akut, keluhan yang dapat muncul berupa kulit dan sklera (bagian putih mata) tampak kuning, kencing berwarna seperti teh, kelelahan, mual, muntah, dan nyeri perut kanan atas. Infeksi akut dapat bertahan selama beberapa minggu kemudian sembuh, atau dapat menyebabkan gagal hati akut yang mengancam nyawa. Infeksi kronik pada umumnya tidak menyebabkan gejala hingga fase reaktivasi, yang memiliki gejala mirip dengan infeksi akut.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis hepatitis B pada umumnya diawali dengan pertanyaan mengenai riwayat penyakit dan faktor risiko terkait. Setelah itu, pemeriksaan fisik dapat dilakukan untuk mempersempit kemungkinan penyakit ini. Gejala hepatitis seperti kuning dapat menjadi penanda penyakit lainnya, sehingga pemeriksaan fisik diperlukan untuk menyingkirkan kemungkinan ini. Dokter dapat melakukan pemeriksaan pada mata dan perut untuk melakukan hal ini.

Jika kecurigaan mengarah ke infeksi virus hepatitis B, beberapa pemeriksaan laboratorium akan dilakukan untuk mengetahui perjalanan penyakit, kadar virus, dan kerusakan hati. Pemeriksaan ini pula yang nantinya digunakan untuk menentukan terapi. Pemeriksaan laboratorium yang dapat membantu deteksi keberadaan virus adalah pemeriksaan antigen pada permukaan virus hepatitis B (HBsAg), antigen pada lapisan terluar virus (HBeAg), antibodi/kekebalan terhadap antigen tersebut (anti-HBe), serta materi genetik virus berupa asam deoksiribonukleat (DNA VHB). Selain itu, pemeriksaan yang dapat dilakukan adalah pemeriksaan enzim hati untuk mengetahui adanya kerusakan hati. Pemeriksaan baku emas untuk mengetahui adanya kerusakan hati adalah biopsi atau pengambilan jaringan hati yang kemudian diamati dengan mikroskop. Pemeriksaan gamma-glutamil transferase (GGT), alkalin fosfatase (ALP), bilirubin, serta protein darah seperti albumin dan globulin juga dapat dilakukan untuk menilai perburukan kondisi hati.

Pemeriksaan terkait kondisi lain seperti infeksi hepatitis C dan HIV/AIDS dapat pula dilakukan untuk mengetahui adanya infeksi yang terjadi bersama atau penyulit terapi.

Tata Laksana

Secara umum, tata laksana hepatitis B bertujuan untuk menekan jumlah virus hepatitis B di dalam tubuh, mencegah penularan dengan vaksinasi, serta meningkatkan kualitas hidup dan keselamatan orang yang terinfeksi. Berdasarkan hasil pemeriksaan laboratorium, dokter akan menentukan rencana terapi hepatitis B. Terapi dapat menggunakan interferon dan obat-obatan antiviral. Interferon merupakan protein yang diproduksi oleh tubuh untuk melawan berbagai virus, bakteri, dan agen berbahaya lainnya. Terapi interferon diberikan melalui suntik dan lamanya dibatasi. Sementara itu, obat antiviral dikonsumsi secara minum dan seringkali harus dikonsumsi setiap hari seumur hidup.

Setelah terapi dimulai, Anda perlu menjalani kontrol setelah waktu yang ditentukan, misalnya dalam 3 bulan. Kontrol ini bertujuan untuk melihat respon terapi. Respon terapi ini salah satunya dipengaruhi oleh kepatuhan Anda mengonsumsi obat. Selain itu, terapi juga dipengaruhi oleh sifat virus sendiri, karena virus kemungkinan dapat melawan obat-obatan yang diberikan, disebut sebagai resistensi.

Jika Anda memiliki penyakit lainnya seperti hepatitis C, hepatitis D, atau HIV/AIDS, Anda dapat diberikan lebih dari satu macam obat untuk menekan jumlah virus yang ada.

Jika Anda adalah seorang wanita berusia subur, penggunaan kontrasepsi sangat dianjurkan untuk mencegah kehamilan, karena Anda berisiko menularkan hepatitis B kepada anak Anda. Jika Anda hamil dan terinfeksi hepatitis B, pengobatan dengan antiviral sangat diperlukan untuk mencegah penularan virus kepada anak Anda. Pengobatan ini perlu diawasi secara ketat, dan pemeriksaan kehamilan perlu dilakukan secara rutin. Setelah bayi lahir, Anda dapat menyusui anak Anda.

Apabila Anda sedang menjalani terapi kanker, terapi penyakit autoimun, atau baru saja menjalani transplantasi organ, pemeriksaan hepatitis B akan dilakukan dan pengobatan akan dilakukan apabila diperlukan.

Komplikasi

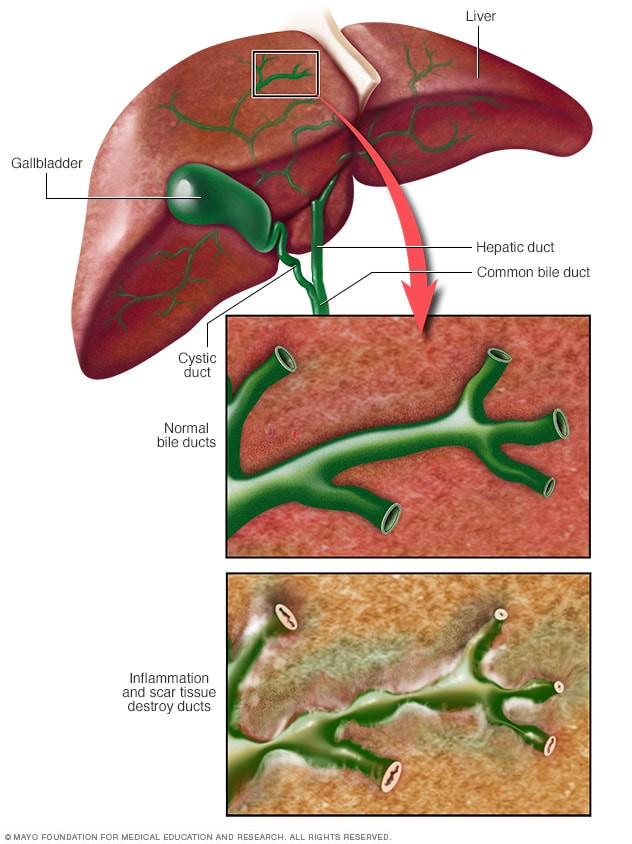

Komplikasi utama hepatitis B adalah sirosis hati (pengerasan hati) yang dapat berlanjut menjadi kanker hati, yang disebut sebagai karsinoma hepatoseluler. Jika Anda sudah mencapai sirosis hati, Anda akan mendapatkan terapi antiviral dengan pemantauan ketat. Anda juga dapat disarankan untuk menjalani transplantasi hati apabila memenuhi syarat untuk menjadi kandidat.

Pencegahan

Pencegahan penularan hepatitis B dapat dilakukan dengan imunisasi. Imunisasi dapat dilakukan secara aktif, yaitu dengan memaparkan bagian dari virus kepada sel kekebalan tubuh, atau secara pasif, dengan memasukkan sel kekebalan tubuh secara langsung. Imunisasi dapat dilakukan pada anak maupun orang dewasa. Berdasarkan jadwal imunisasi dari Ikatan Dokter Anak Indonesia (IDAI) tahun 2020, bayi yang baru lahir wajib mendapatkan imunisasi hepatitis B, dilanjutkan pada usia 2, 3, dan 4 bulan, bersama dengan difteri-tetanus-pertusis (DTP) dan Haemophilus influenza B (HiB). Sementara itu, pada orang dewasa, vaksinasi hepatitis B dapat dilakukan pada orang yang terpapar darah, staf fasilitas cacat mental, pasien cuci darah (hemodialisis), penerima faktor pembekuan darah, orang serumah atau berhubungan seksual dengan penderita, laki-laki yang aktif berhubungan seksual dengan sesama laki-laki atau orang yang memiliki pasangan seksual lebih dari satu, petugas kesehatan, pengguna NAPZA suntik, dan anak yang lahir dari ibu penderita hepatitis B. Vaksinasi ini diberikan tiga kali, pertama saat faktor risiko ditemukan, 1 bulan kemudian, dan bulan ke-6 setelahnya.

Selain itu, pencegahan penularan dapat dilakukan dengan beberapa cara berikut:

- Pastikan seluruh orang yang tinggal serumah dan pasangan seksual sudah divaksin

- Gunakan kondom saat berhubungan seksual terutama apabila pasangan belum divaksin atau memiliki masalah kekebalan tubuh

- Hindari penggunaan sikat gigi dan alat cukur bersama

- Hindari penggunaan jarum suntik berulang

- Hindari penggunaan alat pemeriksa gula darah bersama

- Segera tutup luka terbuka atau gores

- Bersihkan tumpahan darah dengan larutan pemutih

- Hindari mendonorkan darah, organ, dan sperma

Perlu diketahui bahwa orang dengan hepatitis B dapat mengikuti aktivitas layaknya orang normal, tidak pantas mendapatkan diskriminasi di tempat umum, dapat berbagi makanan dan alat makan, serta mencium orang lain.

Kapan Harus ke Dokter?

Segeralah ke dokter apabila Anda atau orang di sekitar Anda memiliki sakit kuning. Sakit kuning belum tentu merupakan hepatitis B, namun dapat menunjukkan adanya kondisi lainnya. Selain itu, apabila Anda memiliki faktor risiko yang telah disebutkan pada bagian Faktor Risiko, segeralah berkonsultasi kepada dokter sebelum hepatitis B berlanjut menjadi sirosis atau bahkan kanker hati.

Mau tahu informasi seputar penyakit lainnya? Cek di sini, ya!

- dr Hanifa Rahma

Hepatitis B. (2021). Retrieved 29 December 2021, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b

Lampertico, P., Agarwal, K., Berg, T., Buti, M., Janssen, H., & Papatheodoridis, G. et al. (2017). EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. Journal Of Hepatology, 67(2), 370-398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021

Lesmana, C., Hasan, I., Gani, R., Sanityoso, A., Djumhana, A., & Setiawan, P. (2017). Konsensus Nasional Penatalaksanaan Hepatitis B di Indonesia. Jakarta: Perhimpunan Peneliti Hati Indonesia.

Terrault, N., Lok, A., McMahon, B., Chang, K., Hwang, J., & Jonas, M. et al. (2018). Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology, 67(4), 1560-1599. doi: 10.1002/hep.29800