Definition

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) is a digestive tract disease characterized by the thickening of the stomach pylorus. This thickening results in a narrowed pylorus gap, creating difficulties for food to pass through to the duodenum. The pylorus serves as the duct connecting the stomach and the duodenum, and when this passage is constricted, the body faces challenges in adequately absorbing nutrients since the primary site for nutrition absorption is the duodenum.

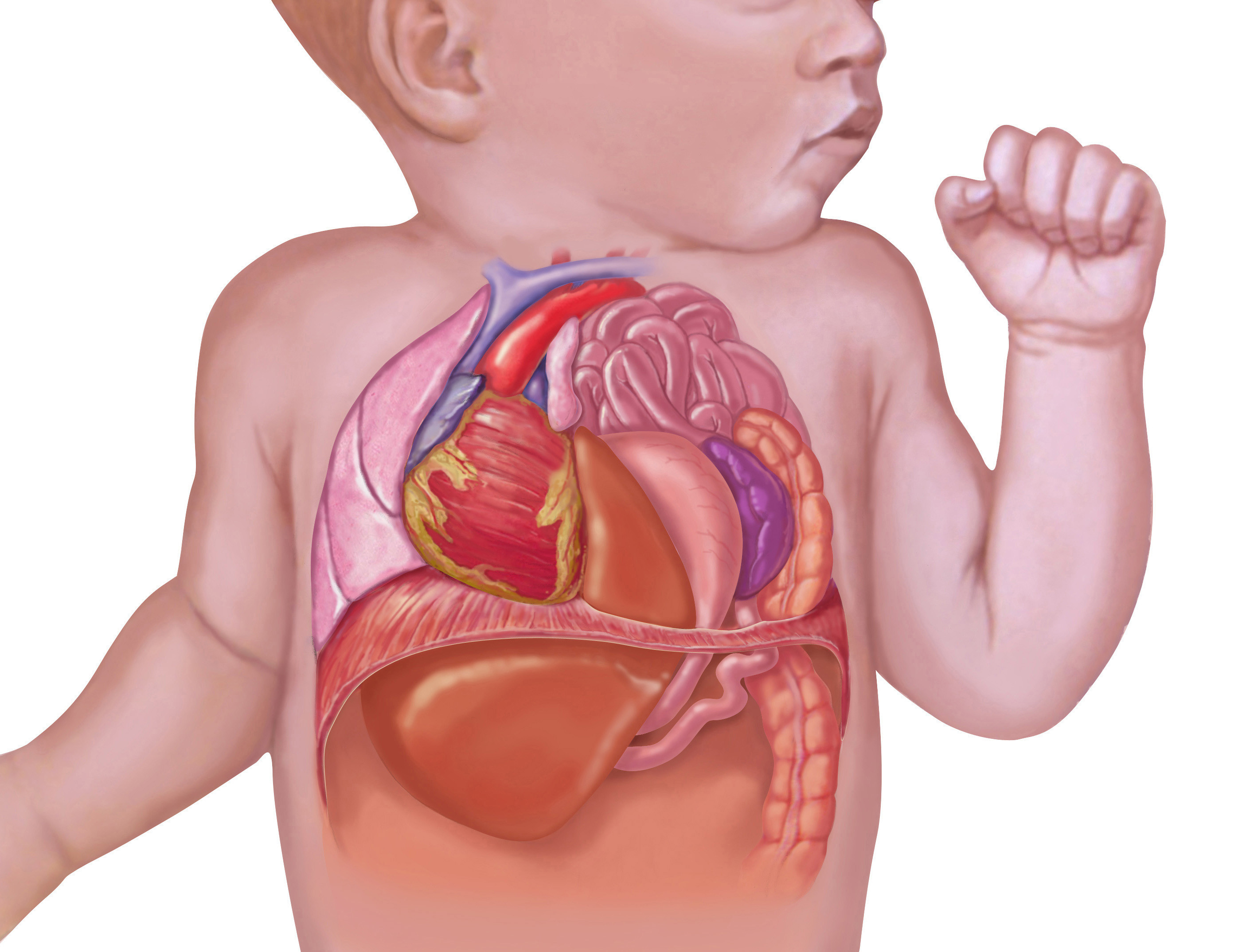

The narrowing of the pylorus prompts an increase in peristalsis movement and the expansion of the stomach as a compensatory mechanism to facilitate the passage of food through the narrowed pylorus into the duodenum. Over the long term, this compensatory response leads to hypertrophy, or the thickening of the stomach muscle.

HPS is typically identified in early childhood, usually between 2 to 8 weeks of age. Additionally, males exhibit a higher risk of developing HPS compared to female children, with a ratio of around 4 to 1.

Causes

The cause of Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis (HPS) remains unknown, but certain theories propose that the thickening of the stomach pylorus is linked to the expression of sphincter levels of insulin-like growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and the growth signaling pathway. These three hormones induce the hypertrophy or thickening of the pylorus, resulting in stenosis or the narrowing of the stomach pylorus. Genetic factors are also considered potential contributors to the development of HPS.

Risk factor

Several risk factors for Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis (HPS) include being the firstborn in the family, the use of macrolide antibiotics within the first two weeks of life, and having siblings with a history of HPS.

Symptoms

The thickening of the pylorus leads to a blockage in the passage between the stomach and duodenum. This obstruction results in projectile vomiting, characterized by the absence of bile in the vomit. The vomit lacks bile because it occurs before the food reaches the intestine.

In children with HPS, vomiting typically occurs after breastfeeding and may be continuous, leading to potential issues of malnutrition and dehydration. Signs of malnutrition include weight loss and delayed growth. Additionally, it's essential to observe for signs of dehydration, such as sunken eyes, dry lips, or an irritable demeanor in the child.

Diagnosis

During the early stages of the disease, Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis (HPS) can be challenging to distinguish from gastroesophageal reflux, potentially leading to misdiagnosis. However, thorough history-taking, consideration of risk factors, and recognition of unique signs such as projectile or spraying vomiting after breastfeeding, along with the absence of bile in the vomit, aid in distinguishing between gastroesophageal reflux and HPS. HPS is more likely to occur in children aged 2-8 weeks.

In physical examinations of children with HPS, an increase in peristaltic movement felt on the abdominal wall, known as the "caterpillar sign," may be observed. Upon palpation, a rounded mass resembling an olive fruit can be felt, termed the "olive sign," located in the epigastric region and capable of being moved.

Due to the increased difficulty in food passage through the pylorus, children with HPS are prone to malnutrition and dehydration, making these signs crucial for diagnosis.

In addition to physical examinations, doctors may perform additional tests. Radiology or imaging, particularly abdominal ultrasonography (USG), is commonly employed. However, the results can vary and depend on the operator's skill. A bull's-eye appearance in the stomach antrum, anterior to the pancreas, is indicative of pyloric thickening and is often referred to as the "doughnut sign" or "target sign."

Alternatively, contrast X-rays can be utilized, revealing a string-like appearance caused by the narrowing of the pyloric gap and a shoulder sign due to the presence of a lump or hypertrophy in the stomach antrum.

Management

Children with Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis (HPS) face a heightened risk of dehydration, making early treatment imperative. Ensuring the child is in a stable condition with adequate hydration is crucial. Administer hydration as per the degree of dehydration and rectify any electrolyte imbalances identified in lab results.

If lab results indicate electrolyte imbalance, particularly hypokalemia, it is likely due to the excessive expulsion of potassium during vomiting. Correcting potassium levels becomes essential to restore electrolyte balance.

The definitive therapy for HPS is pyloromyotomy. This surgical procedure involves the reconstruction of the stomach pylorus to correct the stricture, allowing it to function properly. Children who undergo this treatment generally exhibit a positive prognosis.

Complications

Over the long term, untreated Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis (HPS) can lead to malnutrition due to the difficulty of food entering the duodenum, resulting in inadequate nutrient absorption.

In addition to malnutrition, dehydration is another potential complication. Children with HPS often experience vomiting, and the narrowing of the pylorus impedes the oral intake of water, making it challenging for water to be absorbed in the large intestine. If left untreated for an extended period, dehydration can be life-threatening. It is crucial to promptly recognize and address signs and symptoms of dehydration.

While pyloromyotomy serves as a definitive treatment for HPS, it can carry complications, such as persistent vomiting for more than two weeks. Adequate food and fluid intake should be ensured to prevent malnutrition and dehydration in the child following the procedure.

When to see a doctor?

If your child exhibits the signs or symptoms of Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis (HPS) as described earlier, it is essential to promptly consult a doctor. Pay close attention to signs of dehydration and ensure the child receives adequate fluid intake to prevent the worsening of their condition.

- dr Ayu Munawaroh, MKK

*Nasrulloh, M Hafiz., Jurnalis, Yusri Dianne., Sayoeti, Yorva. 2019. Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis. Jurnal Fakultas Kedokteran Universitas Andalas. Diakses pada tanggal 20 Januari 2022. http://jurnal.fk.unand.ac.id/index.php/jka/article/view/1115

*Ma’ruf, Fauzy., 2019. Pemeriksaan Radiologi Pada Ksus Hipertrophy Pyloric Stenosis (HPS). Fakultas Kedokteran Islam Al-Azhar. Diakses pada tanggal 20 Januari 2022. https://e-journal.unizar.ac.id/index.php/kedokteran/article/view/50.

Medscape (2017). Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/929829-overview.