Definition

Pemphigus vulgaris is a rare autoimmune disorder that causes painful blisters and sores on the skin or mucous membranes, often beginning in the mouth. It is the most common subtype of pemphigus, accounting for around 70% of cases globally.

Other subtypes include pemphigus foliaceus and paraneoplastic pemphigus. Pemphigus is typically a chronic condition, and some forms can become life-threatening without proper treatment.

Causes

Pemphigus is classified as an autoimmune disease, meaning the body mistakenly attacks its own cells—in this case, those in the skin and mucous membranes.

It is non-contagious, and in many cases, the exact trigger is unknown. However, pemphigus may occasionally be triggered by medications, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, cephalosporins, and penicillamine.

Infection or skin trauma may also sometimes initiate the disease.

Risk Factor

Although pemphigus vulgaris can develop at any age, it primarily affects adults aged 30 to 60. It is also more frequently seen in individuals of Middle Eastern, Indian, or Jewish ancestry, possibly due to genetic predispositions.

Symptoms

Early signs of pemphigus vulgaris often involve blisters in the mucous membranes, including the mouth and genitals, with skin blisters appearing after a few weeks or months. In some cases, blisters may only affect the mucous membranes.

On the skin, these blisters are fragile, filled with clear fluid, and easily rupture, leaving painful, itchy sores prone to infection. Common areas affected include the upper chest, back, scalp, and face.

In 50-70% of pemphigus vulgaris cases, oral blisters are present, leading to symptoms like:

- Widespread blisters and sores throughout the mouth

- Painful mouth ulcers that heal slowly

- Difficulty swallowing and hoarseness if blisters extend to the throat

The nasal passages may also be involved, leading to congestion and bleeding. Pemphigus vulgaris can further affect areas such as the eyes, esophagus, lips, vagina, cervix, penis, and anus.

Diagnosis

Since various conditions can cause blisters, diagnosing pemphigus vulgaris can be challenging. Typically, a dermatologist will conduct the diagnosis, beginning with a medical history review and an examination of the skin and mucous membranes. Additional diagnostic tests may include:

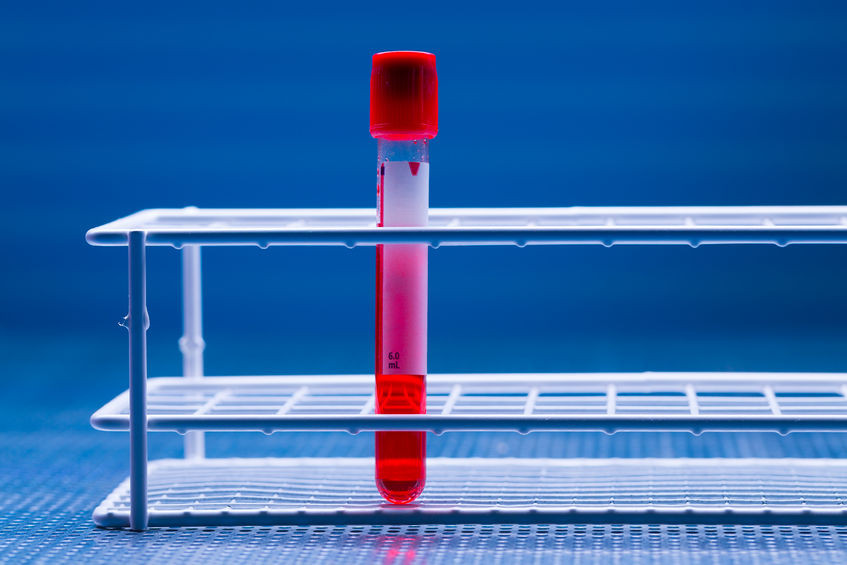

- Skin Biopsy: A tissue sample near a blister is taken and analyzed under a microscope, which is generally necessary for confirming pemphigus vulgaris.

- Blood Test: This test detects specific antibodies associated with pemphigus vulgaris, namely anti-dsg1 and anti-dsg3 antibodies. The levels of these antibodies may help assess the effectiveness of treatment.

- In cases where pemphigus vulgaris affects the throat, an endoscopy may be performed to examine and identify any sores. This involves guiding a flexible tube through the throat for a closer look at affected areas.

Management

The primary objectives in managing pemphigus vulgaris are to reduce blister formation, prevent infections, and support the healing of existing blisters and sores. Treatment usually starts with medications to suppress blister development, and early intervention often leads to better outcomes. If pemphigus symptoms are caused by specific drugs, simply stopping the use of those drugs may alleviate the condition.

Treatment may involve one or a combination of medications based on the disease severity and any other health conditions present:

- Corticosteroids: These are the cornerstone of pemphigus therapy, typically with moderate to high doses of prednisone or prednisolone, or injections of methylprednisolone. Since corticosteroids have been used in pemphigus treatment, the mortality rate has decreased significantly (from 99% to 5–15%). Though not curative, corticosteroids improve patients’ quality of life by controlling disease activity. Long-term or high-dose usage, however, can lead to side effects such as diabetes, bone loss, heightened infection risk, stomach ulcers, and facial swelling (moon face).

- Non-steroidal immunosuppressive medications: Used to reduce steroid dosage, these medications may be necessary for extended periods. Examples include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, and monoclonal antibodies. They help in preventing the immune system from attacking healthy tissues, though they also carry risks like increased susceptibility to infection. Rituximab is now FDA-approved as a primary treatment for pemphigus vulgaris.

Additional medications may be used alongside primary treatments, including dapsone, methotrexate, tetracycline, nicotinamide, plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin, extracorporeal photopheresis, immunoadsorption, and infliximab.

For topical treatment, creams with steroids and moisturizers are available for skin areas affected by pemphigus. Mucosal pemphigus treatments may involve steroid creams, localized steroid injections, tacrolimus cream, or cyclosporine cream. Mild cases can often be managed with corticosteroid cream alone.

While many people with pemphigus improve with treatment, this can take several years, and some may require lifelong medication to prevent relapse. In severe cases, hospitalization may be necessary for wound infections or extensive sores. Even with optimal treatment, mild symptoms may persist.

Complications

Pemphigus vulgaris can cause widespread, potentially life-threatening lesions if not diagnosed early. Possible complications include:

- Infections of the skin (bacterial, fungal like candida, and viral, such as herpes simplex)

- Bloodstream infections (sepsis)

- Nutritional issues due to painful mouth sores

- Side effects from treatment, including high blood pressure, infections, and bone loss

- Psychological impacts, such as anxiety and depression, from severe skin disease and its treatment

Prevention

There is no established way to prevent pemphigus vulgaris, but steps can be taken to reduce blistering, including:

- Avoiding activities that may irritate or damage the skin and mucous membranes, such as contact sports or consuming spicy, acidic, or hard foods.

- Using a soft, mint-free toothbrush for gentle brushing and rinsing with an antiseptic or anti-inflammatory mouthwash.

When to See a Doctor?

Consult a doctor if you develop blisters on your skin or in your mouth that are slow to heal.

Looking for more information about other diseases? Click here!

- dr Anita Larasati Priyono

Pemphigus - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic. Mayoclinic.org. (2022). Retrieved 6 May 2022, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pemphigus/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20350409.

Pemphigus vulgaris | DermNet NZ. Dermnetnz.org. (2022). Retrieved 6 May 2022, from https://dermnetnz.org/topics/pemphigus-vulgaris.

Pemphigus Vulgaris: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology. Emedicine.medscape.com. (2022). Retrieved 6 May 2022, from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1064187-overview.